Current Theories

The family

Equidae has long been held as a classic example of orthogenesis (Gould 1987)

for several reasons:

1) Fossils of Equidae are very abundant (MacFadden 1992). This means that there were enough of them to be studied at the time when evolution was first being studied, and when orthogenesis was the prevailing evolutionary theory.

2) There is only one surviving genus, Equus, which may suggest the concept of an evolutionary "goal" and a single line of evolution (Hunt 1995).

3) Straight-line evolution of horses has been taught since the late 17th century (Gould 1987), which makes it a long-standing theory which is hard to shake from the public consciousness despite scientific evidence that refutes it.

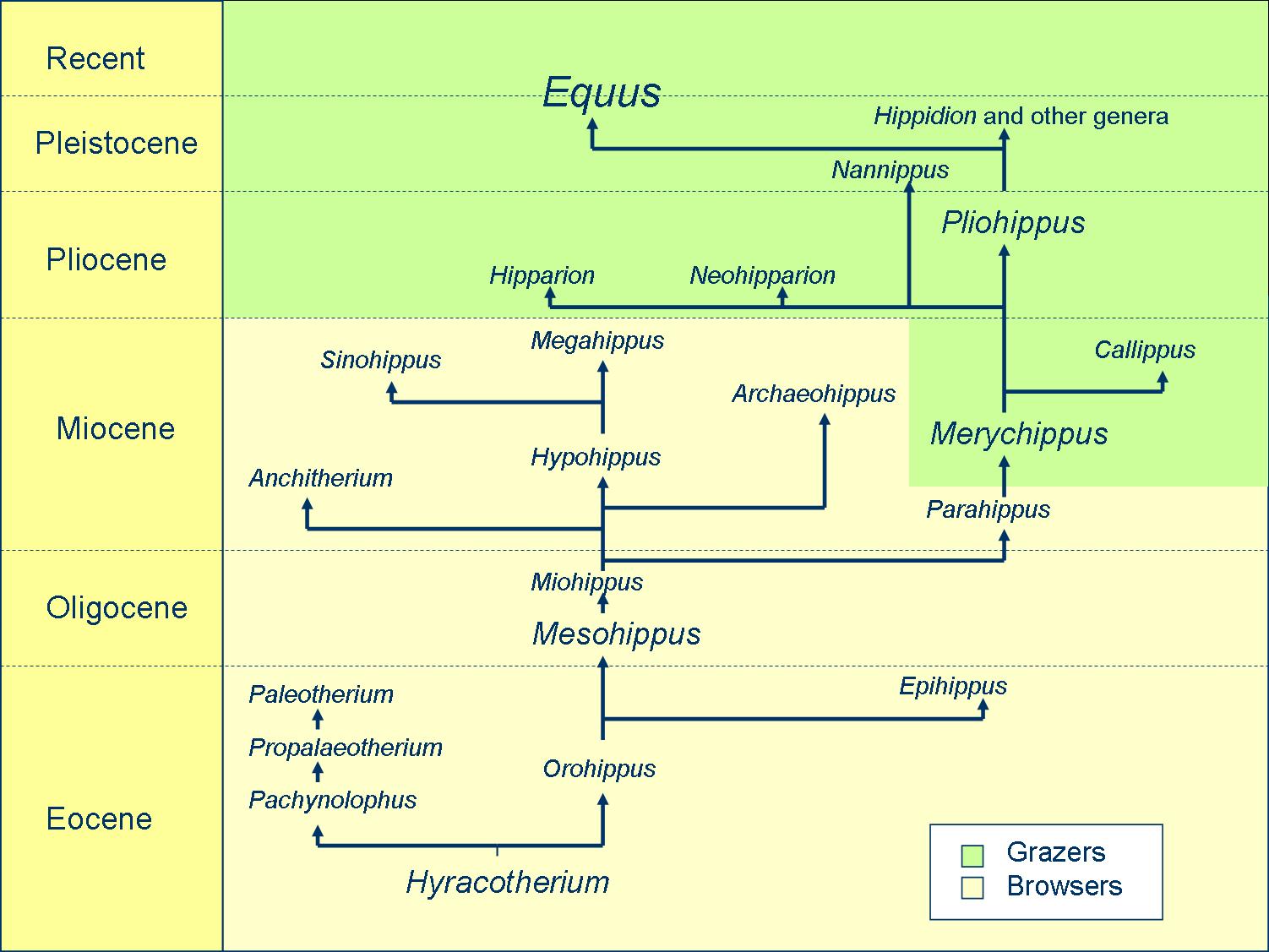

We know now that the evolution of horses did not proceed in a straight line, but in a complexly branching pattern in which many genera may have coexisted (Hunt 1995). Evolutionary change within a single lineage occurred slowly, if at all: most change occurred where one genus branched off into two (Gould 1987). Although a trend of larger size, longer limbs, fewer toes, and longer teeth may have occurred in many different lineages, they did not all occur at the same time or at the same rate, and in some cases did not occur at all (Hunt 1995).

1) Fossils of Equidae are very abundant (MacFadden 1992). This means that there were enough of them to be studied at the time when evolution was first being studied, and when orthogenesis was the prevailing evolutionary theory.

2) There is only one surviving genus, Equus, which may suggest the concept of an evolutionary "goal" and a single line of evolution (Hunt 1995).

3) Straight-line evolution of horses has been taught since the late 17th century (Gould 1987), which makes it a long-standing theory which is hard to shake from the public consciousness despite scientific evidence that refutes it.

We know now that the evolution of horses did not proceed in a straight line, but in a complexly branching pattern in which many genera may have coexisted (Hunt 1995). Evolutionary change within a single lineage occurred slowly, if at all: most change occurred where one genus branched off into two (Gould 1987). Although a trend of larger size, longer limbs, fewer toes, and longer teeth may have occurred in many different lineages, they did not all occur at the same time or at the same rate, and in some cases did not occur at all (Hunt 1995).